The Singles Not Taken

An analysis on the T20 World Cup game : Nepal vs South Africa analysis

With Nepal having qualified for another T20 World Cup, my mind went back to this epic encounter.

Gulshan Jha can’t get his bat on the short ball, but the batters scamper for a quick single. Quinton de Kock fires a throw at the striker’s end and misses. The ball trickles to Heinrich Klaasen, who gathers and underarms it at the non-striker’s end — and hits. Gulshan Jha is short by inches. South Africa win; Nepal lose by one run. Heartbreak for Nepal, who came within touching distance of pulling off a famous upset at the ICC Men’s T20 World Cup 2024.

For Nepali cricket fans all over, the what-ifs were all that remained — “What if the ball hadn’t fallen so kindly for Klaasen so close to the stumps? What if Jha had put in the dive? Then we would be heading to a Super Over. What if we had managed to score one more boundary with only 8 to get in the final over?”

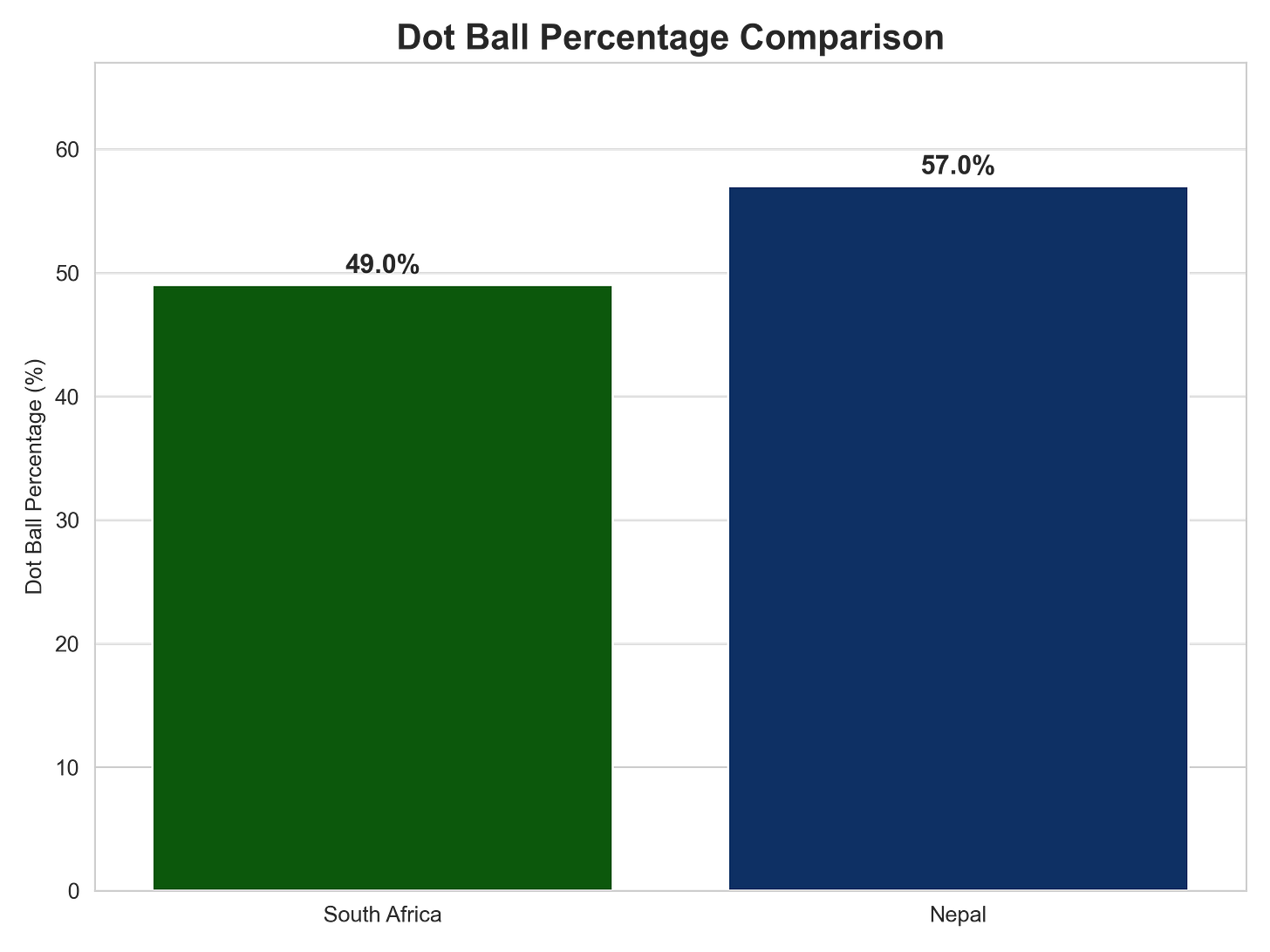

I, being a cricket fan and a Nepali, was gutted and upset that we let it slip. We were so close to an enormous scalp, but were undone at the last hurdle. When the dust settled though, I asked myself: where did Nepal actually lose the game? Was it on the last ball, or — as I’d noticed during the match — was it the far too many dots that ultimately became the major differentiator between the two sides?

The straight answer — yes. Nepal had 68 dot deliveries out of the 120 available, which means 57% of their innings comprised dot deliveries. South Africa had 59 dot deliveries, about 49% of their innings. And as the adage goes in T20 cricket: “Dot deliveries are worth gold.”

The Kingstown pitch that day aided the slow bowlers, and the Nepali spinners put the South African batters under pressure. Airee with his offbreaks, and Bhurtel with his leg spin bagged 3 and 4 wickets respectively. Having bundled out the Proteas for a paltry 115, Nepal began brightly with the bat, 32 for none in the powerplay, built the innings with 62 for 3 in the mid-overs, until it all fell apart in the last five, where Nepal lost four wickets for 19 runs, and ultimately cost them the match.

But underneath, the good powerplay, the stable middle overs, and the collapse, there was a deeper issue that lay dormant.

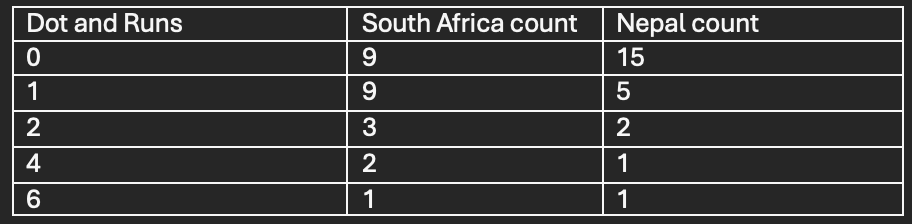

Below, a table of dot deliveries comparison between the two sides:

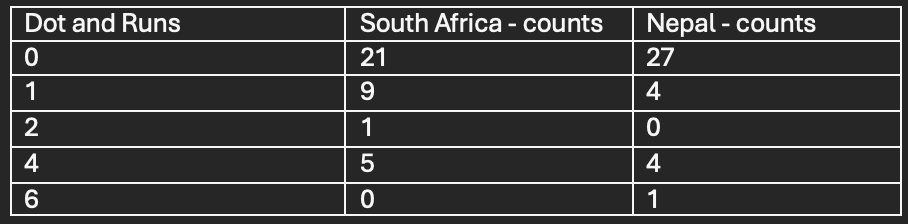

The Powerplays

On the outside, when looking at the Powerplay score, Nepal scored 32 runs in the first 6 overs chasing 115. However, upon closer observation, we see 27 dot deliveries out of 36 available deliveries – that is, 75% were either dot deliveries or extras. What is even more staggering is, Nepali batters scored 26 runs, but off only the 6 deliveries with their bats, the other runs came as extras in the remaining 3 deliveries.

Contrast that to South Africa, who lost De Kock early, still found ways to score and scored off of 6 more deliveries than Nepal.

Upon closer inspection of the runs scored during the Powerplay,

South Africa made sure they got singles and doubles, and even though they did not hit a maximum during the Powerplay, they still outscored Nepal. Nepal could not consistently find the singles, and it was really the extras that kept them closer to South Africa at this point.

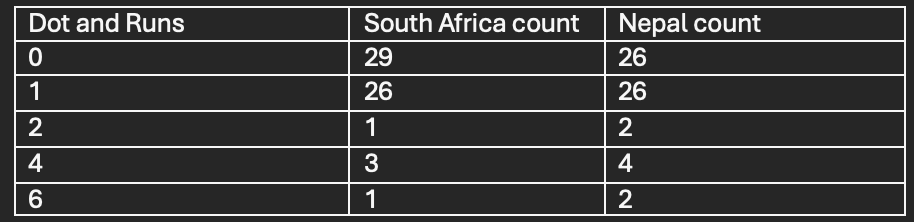

The Middle-Overs

Nepal got some much-needed control in the middle of the innings and outscored South Africa by 16 runs. Nepal also had 3 fewer dot deliveries than South Africa in this stage. But the takeaway here comes when we look at the Delivery outcomes in the runs table:

We can observe how South Africa has scored the same amount of runs in singles as Nepal, despite having more dot deliveries than Nepal. However, take nothing away from Nepali batters; the middle overs belonged to Nepal, and it looked like they were the favorites from here.

The Death-Overs

This is where all the experience and the ability to handle pressure come into play, and it showed. Nepal was the inexperienced side, and the Proteas came roaring back into the game.

Nepal were abysmal again and consumed another 15 dot deliveries in the death overs — criminal, as they say. Fifty percent of the deliveries were dots at the tail end of a tight chase.

South Africa, clearly with their vast experience, built their innings towards the back end in the death overs. The consolidation in the middle overs meant they could push on in the final five. And even though it was not a big push towards the end, the singles mattered in the end.

Nepal did not lose that fateful day in the last over, nor because Jha did not dive to make his ground. Nepal outscored South Africa in boundaries by 8 runs, having scored 9 fours and 4 sixes (60), to South Africa’s 10 fours and 2 sixes (52 runs). But South Africa had 44 singles to Nepal’s 35, and outscored Nepal by 9 runs in singles.

It is that margin of one run between the boundaries and the singles that separates the two sides — the margin between victory and defeat.